Alternative Scenarios to the U.S. Hegemonic System

Authors: Rozem Dila, Catalina Pérez Chica, Esteban Reyes Guzmán, Sarah Zebalos Cipolli

Keywords: Hegemony, United States, Democracy, Realism, Geoeconomic fragmentation.

The United States has dominated the international system for decades, but as emerging

powers reshape global politics, is the world shifting toward a new order? Promptly after the Cold

War, the U.S. established itself as the chief supporter of global security, with NATO serving as

the main forum. However, recent remarks by President Donald Trump have cast doubt on the

sustainability of this role. In February 2024, Trump suggested that the U.S. might not defend

NATO allies, even saying that Russia could “do whatever the hell they want1” to those nations.

This occurrence signals a potential shift in U.S. foreign policy, one that correlates United States’

approach before World War II, when the U.S. pursued an isolationist stance, avoiding engaging

in European conflicts until necessity dictated otherwise, and today, as economic pressures,

domestic political shifts, and geopolitical rivalries challenge U.S. dominance, a new

transformation is possible. If the United States is pulling back from its traditional leadership role,

what alternative structures could emerge in the international system? This paper explores the

future of global governance in a world where U.S. hegemony is no longer given, analyzing

regional power dynamics, security alliances, and shifting geopolitical frameworks through an

academic perspective.

Post-Cold War World Order

With the end of the Cold War in 1991, the dissolution of the bipolar international system

and the emergence of a unipolar world made the United States the uncontested leader. Once no

longer constrained by the Soviet Union, the U.S. expanded its influence through a network of

military alliances, economic liberalization efforts, and the promotion of liberal democratic

values. The U.S characterized this “unipolar moment” with military interventions, such as in the

Gulf War, Kosovo, Afghanistan, and Iraq, and also the enlargement of NATO to include Warsaw

Pact countries, and the institutional dominance of organizations like the International Monetary

Fund (IMF), World Bank, and World Trade Organization (WTO). These institutions, often

shaped by Washington Consensus policies, facilitated the global spread of free-market

capitalism, reinforcing U.S. economic and ideological supremacy. Moreover, the United States

maintained a strategic global military footprint, with forward-deployed forces and security

guarantees across Europe, Asia, and the Middle East. Politically, it positioned itself as the

defender of a liberal international order, underwriting global stability under its leadership.

In whatever way, like all great powers throughout history, the U.S. always faced supremacy

challenges. Comparatively, as the Cold War saw the world structured around two competing

blocs–the U.S.-led West and the Soviet sphere–the 21st century is witnessing the rise of

alternative power centers, particularly in Eurasia. China’s economic and military expansion,

Russia’s geopolitical assertiveness, and the increasing influence of regional alliances suggest that

the unipolar moment may be facing its downfall.

Declining Integration During the U.S Hegemony

Over the last decades, economic and political landscapes have undergone rough shifts,

proved by inclinations towards protectionism alongside evolving geopolitical dynamics. Rising

state intervention and radical swift of trade relations reflect broader and strategic realignments,

with the polyvalent role of the United States in matters of global shifts in diplomatic relations.

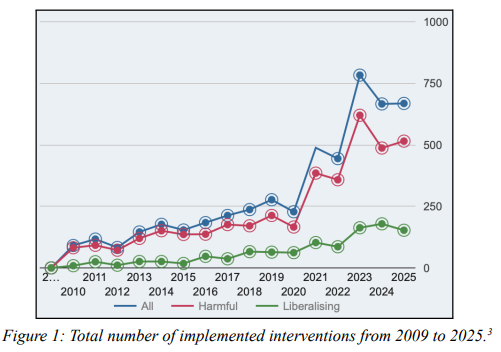

Nevertheless, this pattern is not solely driven by the major protagonists. Indeed, as shown by

Figure 1, starting from the 2008 Great Recession, governments worldwide have implemented

3775 interventions against foreign commercial interests, contrasted just by 1075 liberalizing

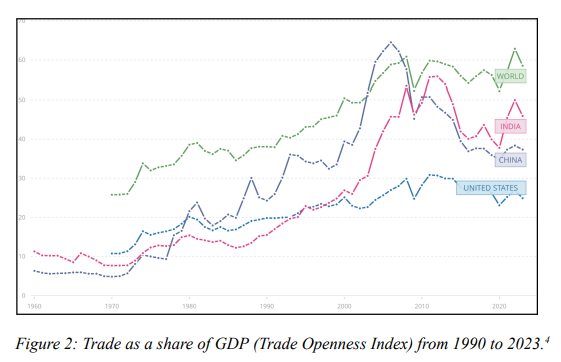

policies2. This phase has also witnessed a relative decline in trade-to-GDP trends compared to

earlier periods. As of 2023, there exists a particular emphasis on the downturn of India and China

(Figure 2).

3 Taken from The Global Trade Alert, Global Dynamics (2025)

4 Taken from multiple sources, compiled by the World Bank (2025)

The distinction from the rising tendency before 2008 has coincided with broader strategic

considerations, reflecting how economic measures intersect with supply chain vulnerabilities and

national security concerns, thus shifting diplomatic priorities. Indeed, U.S. policy ramifications

extend beyond trade and have been a key factor in shaping this evolving landscape. The outcome of the Trump Administration’s front-runner choice concerning the imposition of tariffs (against

Canada, Mexico, and China) and the erosion of previously negotiated exemptions with its allies

has turned out to be even more controversial as sanctions on Russia have been extended without

U.S. participation. A proper explanation may be found in the disruption of long-standing energy

ties between Russia and Europe, forcing a realignment of global energy markets. Meanwhile,

strategic competition with China has intensified in the field of technology and security policy,

with tensions manifesting in heightened military presence in the Indo-Pacific, and efforts to build

stronger partnerships with allies in Asia and Europe.

The exemplification of political fragmentation inclinations regarding the changing dynamics of

the Russo-Ukrainian conflict and the strategic U.S.-China rivalry have contributed to an

escalation of geopolitical tensions and, thence, the erosion of traditional diplomatic linkages that

have been the implicit common rule governing international relations. As a consequence, these

disruptions from traditional trends reflect a shift from a globally integrated economy towards a

more fragmented geopolitical landscape, paving the way for emerging frameworks as an

unconventional arrangement that may respond to the nowadays political and economic panorama

in an increasingly multipolar world.

Current Political Panorama and Democratic Decline

As already mentioned in the previous sections, the United States’ role is changing on the

economic and political fronts, questioning the current efficiency and decoupling at a global scale

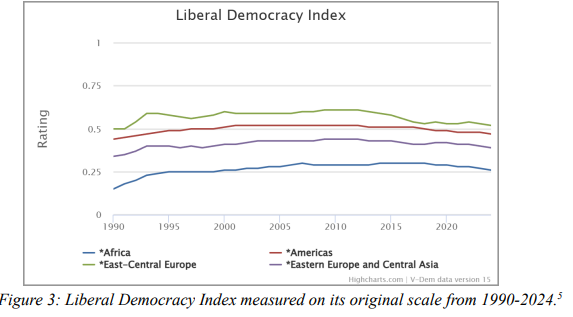

on this basis. As demonstrated in Fig. 3, there is a subtle yet indicative change in domestic

political organization in most of the regions of the world.

5 Taken from V-Dem (Coopedge et. al) 2024.

The previous graph measures democratic decline at a domestic level and aggregates it to a

regional measure, observing respective autocratic or democratic trends in the electoral process

and protection of personal freedoms against the government (Coopedge et. al). The change

corresponds to the political landscape post-Cold War, for instance, the fact that countries are

recently seeking to trade with politically aligned nations rather than prioritizing economic

efficiency (source article). The so-called geoeconomic fragmentation coupled with disruptions

such as the US-China tensions and the Russo-Ukrainian war accelerate this process, leading to

reshaped trade flows but most importantly highlighting a possible change in the international

system. Even though the indicators and general behavior are showing a possible change, the role

of the U.S. remains constant, as the major change is the slowing of global growth rates.

In purely geopolitical terms, the scene is less subtle than the current economic panorama. Two

major case studies stress the role of the U.S. as a possible declining power: The role of NATO in

the Russo-Ukranian War and the presence of China in the Global South along with the reinforced

Sino-Russian alliance. Historically, the North Atlantic Alliance was done as a defensive military

front to answer the Russian question, but today, it shows the weakness of the U.S. umbrella of

military power. A prime example is the recent EU initiative, ReArm Europe. Even if the

Russo-Ukrainian war is not a proxy conflict–per se, the current political order is made of the

U.S. protecting Europe and Europe allowing a degree of meddling so that the U.S. does not

become a marginalized power. The late and rather inefficient activity of NATO in this conflict

questions that ability, leading to initiatives that could–intentionally or unintentionally–undermine

the role of the U.S.

Logically if the European Union can no longer count on the U.S. for security, their response must

be swift, thus we have initiatives such as ReArm Europe that seek to harness outdated military

power. Coupled with the current Trump administration’s threats of pulling from NATO and other

key geostrategic points/conflicts, France stands as a possible leader to harness that military

power, being the only European nation in the Nuclear Club. On the other front, China harnesses

soft power in the Global South, especially with initiatives such as the BRI (Belt and Road

Initiative) that seeks to unite Eurasia through railways. The U.S.-China breakdown now

transcends economic disputes and war of knowledge and is evolving into a direct conflict as

third-class countries are seeking to challenge the traditional U.S. liberal order for the

economically beneficial China. In the scenario that our prediction becomes fulfilled, there are

possible alternatives that are to be explored in the following section.

Proposition of an Alternative Structure to the U.S Hegemonic Role

The contemporary international system is best understood through a realist approach,

fundamentally grounded in the principles of anarchy, state self-interest, and power balancing.

Following this framework, the future of international relations is shaped by the dominance of

realism, where power politics remain at the core of global interaction. Consequently, states will

focus on maximizing their power to secure their survival, as envisioned by classical theorists

such as Hobbes and Morgenthau. The increasing militarization, rising nationalism, and economic

protection of the current geopolitical climate reinforce the persistence of logic.

Because the future of international relations is likely to be shaped by the continued dominance of

realism, maximizing political power to secure influence with increasing militarization, rising

nationalism, and economic protectionism; regionalism emerges as a strategic response from

states that seek to consolidate power and enhance security by forming multilateral alliances that

strengthen their influence in an increasingly fragmented world. The multilateral framework

anchored by global institutions, such as the World Trade Organization, may well evolve in

response to the already-mentioned erosion of traditional linkages, paving the way for a new era

marked by more regionally tailored agreements. As stated in the previous sections, an indicator

of these relations would be the reinforcement today of the Cold War alliance system. Since the

landscape of International Relations is grappling with fresh challenges, considering geographical

proximity and common interests, coupled with the increasing nationalist trends, a regionalist

approach provides a framework for an alternative U.S. hegemonic system, highlighting economic

interdependence, local autonomy, and collective security.

Although it may seem contrary to the spotlight on realism, some elements of neo-functionalist

theories might be accommodated, as they postulate that successful regionalism is proportional to

the extent to which states respond to interdependence pressures by transferring national

sovereignty to regional governance mechanisms. In other words, while realism prioritizes state

sovereignty and national interests, it does not entirely impede functional cooperation for strategic

objectives. Hence, limited sectoral integration could still emerge as a pragmatic response to

shared challenges, as long as it reinforces state power rather than lessening it. Since regional

integration involves the transformation of expectations and dynamics, it is evident to consider the

Regional Security Complex Theory (RSCT), which is based on the assumption that the regional

level is the basis for security analyses due to the geographical proximity of interactions and

threats; besides appraising the coexistence of five sectors in which security relations are

considered: political, military, economic, social, and environmental.

Ultimately, the proposed alternative structure may be outlined in the conception of a new model

devised as the Regionalized Multipolarity Framework, using regionalism as an organizing

principle to replace U.S. hegemony through a multi-regional global order in which power is

balanced through regionally anchored governance systems; by merging four different pillars

focused on outlooks from a revamped RSCT and redefinition of the current functions of

institutions of global governance.

Since the RSCT fails to notice geographic areas where the states’ failure to function at the

regional level involves the absence of any form of security interdependence, the new framework

features adjacent great powers naturally penetrating nearby regions to address shared security

externalities. Thus, considering a proximity-based approach, regional powers are allowed to take

roles in organizing security and reducing the requirement for a hegemonic power like the U.S. to

intervene directly from afar. Hence, adjacent great powers act as hybrid actors, simultaneously as

regional and global participants in regional security dynamics.

This is, indeed, China’s involvement in Central Asia, depicting its interest in securing its borders

and keeping stability in its specific region. Correspondingly, this new groundwork minimizes the

tendency to overestimate the role of world powers as agents that decide on the level of security

globally.

In the same context, another factor encompassed by the proposed model lies in sovereign poles

based on regional coalitions, aimed at organizing each region around a bloc with a clear

governance structure, modeled after successful cases such as the European Union or the ASEAN

(poner significado). Therefore, for the remaining areas around the globe, there might exist a

union of the AfCFTA (African Continental Free Trade Area) and African Union; a remodeled

Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) to balance Sino-Russian geopolitical interests; and

even a restructured MERCOSUR and UNASUR for the South American region.

The new framework must deliberate on the relationship regarding the devolution of sovereignty,

devising the relevance of cooperation benefits and costs to define ideal types of regionalism

depending on the geographical proximity and ideological complexity of the potential member

states. Specifically, in the case of considering status-driven motivations, the emergence of

symbolic regionalism is focused on building the legitimacy of state members towards external

audiences with possible institution-building for political correctness. On the other hand,

autonomy-oriented regionalism may be the front-runner option used to contest external

hegemons, as it is used towards endorsing mutual regime support. Lastly, by applying

transnationalism, regionalism may be based on addressing interstate policy issues, namely, many

of the current common market initiatives on a global scale.

Final Remarks

The evolution of the international system toward an alternative framework is becoming

an increasingly tangible reality, as multiple structural factors converge. The internal political

shifts within major powers, notably the United States, the reinforcement of defensive alliance

systems across the Indo-Pacific, and the intensification of geoeconomic fragmentation

collectively signal a departure from the post-Cold War unipolar order. Within a contemporary

realist framework—marked by the partial erosion of globalization—regionalism and

multipolarity emerge as the most plausible organizing principles of global politics. As previously

outlined, the redefinition of power distribution will likely be anchored in proximity-based

security complexes and sovereign regional poles, redefining the role of global governance

institutions. Thus, the central issue is no longer who dominates the current international order, but rather who will shape the architecture of the world to come.